I sat down with Rabbi David, the Wesleyan Jewish Chaplain, to discuss the religious significance of the tallit and the way that the tallit is used throughout the Jewish lifetime. We talked about how the tallit is at once significant within one Jewish life and has always been ever-present throughout the entire history of the Jewish people.

We’ve got these things like tallitot. You know, like, when my first son was born, we pulled out the chuppah, and it happened under the chuppah poles. It tells us, we’re in sacred time, I’m with my Jewish family, and we’re in the realm of the sacred. And so it’s genuine and it’s authentic. And it connects me with my purpose and connects me with my people.

Rabbi David: “It is with the tallit that I may ask and answer: How do I remind myself that I am part of a people and I have a way of being in the world that is Jewish? I look at the fringes and I remind myself of the way I’m supposed to be in the world.

It’s physical, I embrace it, and I take shelter in it. I immerse myself in this safe space, of recovenanting and reconnecting with a tradition.

It reminds me of the version of myself that I want to be.

It reminds me physically, and it has a shared memory of this echo of tradition. Oh, I’m part of a people. I may be depressed and miserable. But oh, I’m part of the people, and our people have put on these garments before and I’m supposed to find inspiration and grounding in a world that is constantly destabilizing.””

Sam: And so how does that personal than sanctity tie into this? When you’re part of something larger? How do you find this personal connection between yourself and your tallit?”

Rabbi David: “So, both/and. I derive meaning in knowing that Jews everywhere, many Jews in different places, are also putting on tallitot this connects them. So I’m part of something beyond me.

I can carve out time, where I am, in some ways beyond space and time, I’m in my own bubble, Literally. It is dark, you can create a cave, right? If you take a few seconds to wrap yourself. So it’s a reminder, it’s a “Oh, okay.” And my body, I have muscle memory now. My mind and my body remember the tallit. So, individual.

And then collective: א ש ר ק ד ש ן, Asher kideshanu – “Praised is the divine, who commanded us” These are in the plural. Everyone should take on this… is it an obligation? Is it an opportunity? Is it a vehicle towards holiness? But yeah, the individual and the collective, both/and.”

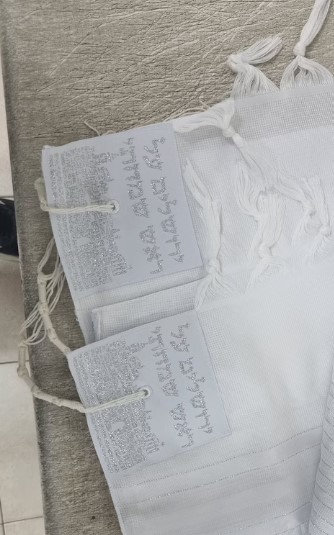

There is a concept in Judaism called the הידור מצוה Hiddur mitzvah, the beautification. It is a commandment to beautify Jewish life and buy artist-quality, beautiful stuff. Right? And then I think you have artists saying this is a moneymaker. Right? You have an industry now that wants to cater to that. I love it. I think it’s one of the neat things and stuff, as opposed to getting a dead person’s tallit that you never met that again, and get a grandfather’s going to pass on a dirty, stained tallit to a granddaughter. This is part of a consumer culture, but it’s also part of an aesthetic.

Sam: Would you say that these objects are intended to elicit a similar feeling to all people who encounter them? Or is it personal, like eliciting a memory, or that personal desire to be an ethical person?

Rabbi David: “I think it depends. I mean, so much of organized religion has become this robotic, stale. “I’m commanded to do it, how quickly can do it?” Like, Okay, I’ve got 10 minutes.”

As humans, if we don’t find ways to disconnect from technology, and to connect with things beyond ourselves, nature, people, tallits… We’re done.

So, then, it’s finding what it is that connects me to something larger than myself. That puts me in a place where I’m no longer instrumentalist, and I’m not performing anymore. I’d like to think that on a good day, I’m not putting on a tallit for the divine presence. Its me alone in the room as the sun is rising. There’s those that say that you pray because God wants prayer.I really don’t think that the divine force in the world needs me to say how great the Divine is. I don’t believe that. I might find humility in myself, in realizing that there might be a bigger world outside of my little cocoon. And so yes, the tallit for me is reminding myself of what really matters, reminding myself of the suffering and the beauty in the world.

And it’s habitual. And it’s a pattern. I don’t do it on Shabbat, but it’s six days a week, it’s in the same place. When I was a kid, I was putting on a tallit on an airplane in 33B next to a whole bunch of people because I had to say it before 12 o’clock, and that’s when my flight was, and it was really weird. But I felt that this is what I need to do. The power of ritual is really kind of neat. There’s something beyond the mystery of it all. That’s also part of it. Once you start analyzing and deconstructing it, the magic is gone. You know, the tallit is sacred, full stop. But there is the power of tradition and the power of reconceiving of what the tradition was.

Sam: I think it’s just something you deliberately devote yourself to. You don’t just spare a thought while checking emails, we think we can multitask. But actively choosing not to and carving out that time carving out a space, saying, I’m going to create a sacred space. Here, wherever here is.

Rabbi David: “When there was a temple we had priests and we outsourced stuff. When the temple got destroyed for the second time, we now have this concept of portable sanctity. I don’t have the temple. But guess what? Let’s go meet at a synagogue. Let’s go put on a tallit. I can sanctify this space. I can sanctify this space. I can put on my tallit, I can create a safe space, I got four corners. But I’m in my little safe space cocoon, but I’m connected to a diaspora, to a people.

With a tallit, you can put people under it. You can wrap your loved ones in it. You can share it.