“Nothing Sacred”: Transformation of historical narratives and their material manifestations in post-Soviet Bishkek

Newspapers are “first drafts of history”. The collaged drafts below represent over 30 years of public debate and collective anxiety about Kyrgyzstan’s Soviet past and post-Soviet national identity. Headlines contest over preservation of Soviet infrastructure: monuments, statues, cemeteries; narratives clash and fall in layers forming a thick canvas of assembled history.

“Nothing Sacred, or When Bolsheviks Stole The Cannons…” Yevgeniya Martyanova, May 25, 2016

NOTHING SACRED

or When Bolsheviks Stole The Cannons…

chronicles of our corner

In Bishkek, there stands a monument whose history is no less intriguing than the events it commemorates: The Red Guards Memorial in Oak Park. Every Bishkek resident is familiar with this tall granite obelisk mounted on a pedestal surrounded by four cannons. But not many know how these cannons got there in the first place.

The monument introduces itself: “Here lie the Red Guards who perished in 1918, fighting the counter-revolution in Pishpek county.” These words are inscribed on one of the granite panels at its base. Yet there’s not a word about the monument’s connection to one of the largest anti-Soviet uprisings in the region–the Belovodsk rebellion.

So, let’s start from the beginning and look back nearly one hundred years.

In those times, the territory of modern Central Asia wasn’t divided into separate independent states. The lands of modern Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan constituted the Western Turkestan region, which joined the Russian Empire in 1867 (joined voluntarily, it’s worth noting, to be protected from the invasions of the Khanate of Kokand). The demarcation of countries and the formation of Soviet republics, including the Kyrgyz Soviet Republic, occurred later, in 1924-1925.

The beginning of the 20th century brought about momentous changes and challenging times. In 1917, the Russian Empire was shaken by revolutions. The Tsar abdicated his throne (after losing his family and his life). Bolsheviks established Soviet power throughout the country, including Western Turkestan.

In March 1917, the Council of Peasants was created in Pishpek.

Bolshevik ideas found support in Pishpek county, but they also had many opponents, mainly among the wealthy peasants. First World War… The country was in chaos, with production shrinking while military expenses were increasing. The state kept squeezing people dry, conducting the so-called prodrazvyorstka, forcefully collecting a set quota of produced goods from the population. Whether you liked it or not, you had to give up what you owned.

In the Semirechye province, revolts among the discontented residents periodically erupted. The Belovodsk rebellion became the largest anti-Soviet uprising of its time in Turkestan.

It all began in December of 1918 in the Belovodsk village, located in the present-day Moscow district of Kyrgyzstan’s Chu Region. At the time, the population of Belovodsk mainly consisted of kulaks, wealthy peasant settlers from central regions of Russia. The interests of these prosperous peasants were represented by the left SRs party, whose members effectively led the rebellion. The White Guards opposing Soviet power also supported the uprising. Therefore, in many sources, the Belovodsk rebellion is called the White Guards SR-kulak uprising.

It should be noted that a few days before the uprising, the rebels requested help from the indigenous population; however, the Kyrgyz people did not support the rebellion.

On December 7, the rebels held a meeting in Belovodsk where they decided to overthrow the Soviet power in Pishpek and the neighboring counties. Right after the meeting, the rebels disarmed the local militia and the unit of Red Army soldiers that arrived from Pishpek. Blood was shed; the rebels killed the Bolsheviks and supporters, including a magistrate.

On December 14, squads of several thousand rebels advanced to Pishpek. According to reports, the Pishpek garrison consisted of 350 Red Army soldiers at the time.

On December 15, the Council of Deputies of the Aulie-Ata County (there was once such a county in Syr-Darya Region; the city of Aulie-Ata is now Taraz) urgently telegraphed to Tashkent that “the rebels have been joined by the nearby villages of Nikolayevsk, Voznesensk, Alexeyevsk, and Kara-Balta,” and requested to send “two machine guns and fifty soldiers” to reinforce the city garrison. The garrison was outnumbered, and the rebels occupied the western part of Pishpek.

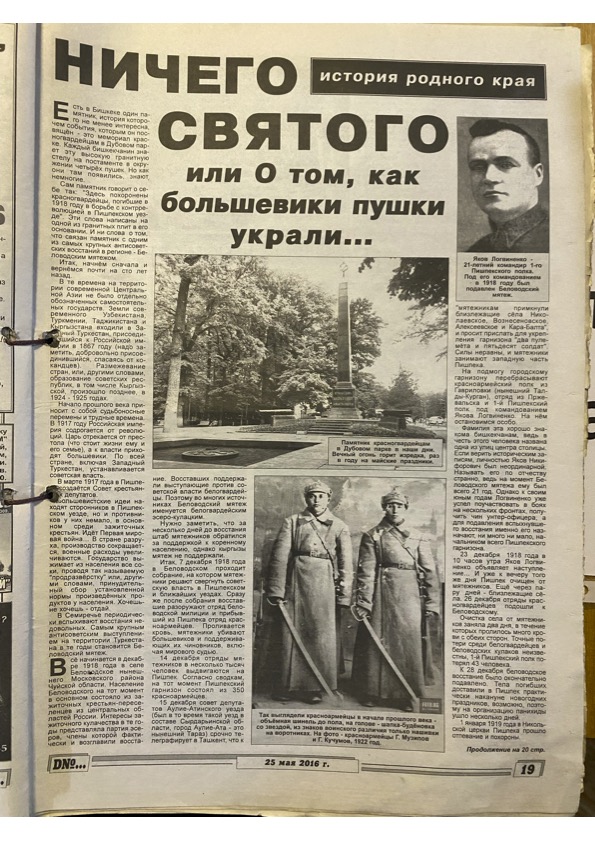

A number of military units were sent to strengthen the city garrison: the Red Army regiment from Gavrilovka (now Taldykorgan), a unit from Przhevalsk, and the 1st Pishpek Regiment under the command of Yakov Logvinenko. Let’s pause on him for a moment.

The last name Logvinenko is well-known to Bishkek locals, since one of the major streets in the downtown area is named after him. According to historical records, Yakov Nikiforovich was an extraordinary individual. It’s odd to refer to him by his patronymic – Nikiforovich, since at the time of the Belovodsk rebellion, he was only 21 years old. However, at this young age, Logvinenko had already participated in battles on several fronts and attained the rank of a non-commissioned officer. For the mission of suppressing the rebellion, he was appointed no less than commander of the entire Pishpek garrison.

On December 23, 1918, at 10 in the morning, Yakov Logvinenko ordered an attack… By that evening, he had cleared Pishpek of rebels. Just a couple of days later, he cleared the surrounding villages, as well. On December 26, Red Guard units approached Belovodsk.

Clearing the village of rebels took them two days, and much blood was shed on both sides. The exact numbers of casualties among the White Guards and Belovodsk kulaks are unknown; the 1st Pishpek Regiment lost 43 men.

By December 28, the Belovodsk uprising was definitively suppressed. The bodies of the deceased were brought to Pishpek practically on the eve of the New Year, which probably explains why it took several days to organize a memorial service.

On January 1, 1919, a funeral service and burial took place at the Nikolayev Church in Pishpek.

The church building still stands in its original place in Oak Park, although it is currently used for a different purpose. In those years, Oak Park (then called Oak Garden) was a center of bustling urban life. It was a place where people organized protests and Orthodox parishioners came for church prayer. This park was chosen as the place to bury the Red Army soldiers who died fighting the rebels.

Initially, the fraternal grave was just a mound, a small barrow with a two-meter obelisk, and a red flag. But the Bolsheviks found this insufficient–they wanted more grandeur. That’s when someone came up with the “bright” idea of placing military cannons on the fraternal grave. Only the Pishpek defenders of the Soviets had no spare cannons of their own, nor did they have the money to buy new ones. So the Bolsheviks found a solution–they stole the cannons from another cemetery. “Well, can we really call that stealing?!” you might ask. But when someone takes something that doesn’t belong to them, especially from a cemetery, what else can it be called?

The raided burial site was not just anyone’s grave. The cannons stood on the grave of Pishpek’s first mayor, Ilya Terentyev–a man who had done much good for the Kyrgyz capital. Under his leadership, the old dusty fortress turned into a flourishing garden-city, where schools, hospitals, libraries, and a theater had been opened. Terentyev devoted most of his life to developing the city, until he passed away in May 1914. On his grave, grateful citizens installed four cast-iron cannons specially ordered from St. Petersburg and delivered to Pishpek.

At the start of the last century, the old Pishpek cemetery was located where the semi-ruined Issyk-Kul movie theater now stands. As we know, Bolsheviks continued their “glorious tradition” of robbing graves in the 1950s, and they literally built this entertainment center on bones. But few people remember that, adjacent to the city cemetery, there used to be a so-called “master cemetery”, a place for the burial of honorable citizens, similar to the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow. It spread between the southeast corner of today’s Ivanitsyn-Ibraimov intersection and the southwest corner of Ivanitsyn-Gogol streets. It was in this cemetery that the first Pishpek mayor Ilya Terentyev was laid to rest. He was buried with the respect and the recognition that the four cast-iron cannons on his grave were supposed to memorialize.

In their original configuration, the cannons had wheels. But for some reason, the Bolsheviks took only the barrels of the cannons; perhaps they couldn’t transport them whole, or maybe they couldn’t destroy the foundation on which the wheels were embedded. Today, we can only guess their true reasons, but the fact remains–the grave of the first Pishpek mayor was ruthlessly robbed.

The cannons were placed at the Red Guard Memorial in Oak Park, and a low fence was put surrounding the mound. However, the burial story didn’t end there. In 1933, the collective grave had a new addition–the same young commander of the Red Guards, Yakov Logvinenko, was buried there. After all the revolutions, he graduated from the agricultural university in Tashkent, returned to the Kyrgyz Republic, and worked as a regular agronomist. Ironically, having fought and survived in several battles, Logvinenko died in 1933 from illness.

In this form as a small mound behind the fence, the monument stood until November 1957. That year, the Soviets decided to give it more gravitas and erected right on the mound an 11-meter obelisk made of red granite with a hammer and sickle on top. At the bottom of the obelisk, they placed panels bearing the names of Red Guards who perished suppressing the Belovodsk rebellion, along with an inscription: “Eternal glory to those who fell in the struggle for Soviet power.” At the corners of the pedestal they put the Terentyev’s cannons.

But we’re still not at the end of our story. On May 9, 1970, a new Eternal flame memorial was opened on the western side of the obelisk. Over time, the townspeople forgot all about the Belovodsk rebels and Red Guards. Instead, they began to associate the monument with Victory Day. People brought flowers to it, newlyweds visited the memorial, and during the day, a Pioneer guard stood watch at the Eternal Flame.

Today, the Eternal flame in Oak Park doesn’t always burn. This year, the city authorities lit it briefly for the holidays on May 6–15. Unlike the Eternal flame in Victory Square, which, as we know, is supplied with gas by LLC Gazprom Kyrgyzstan at its own expense, the flame at the Red Guards Memorial is on the budget of the city hall. And this year, it seems like our city representatives were shot out of a cannon to fund the Eternal flame for an entire week.